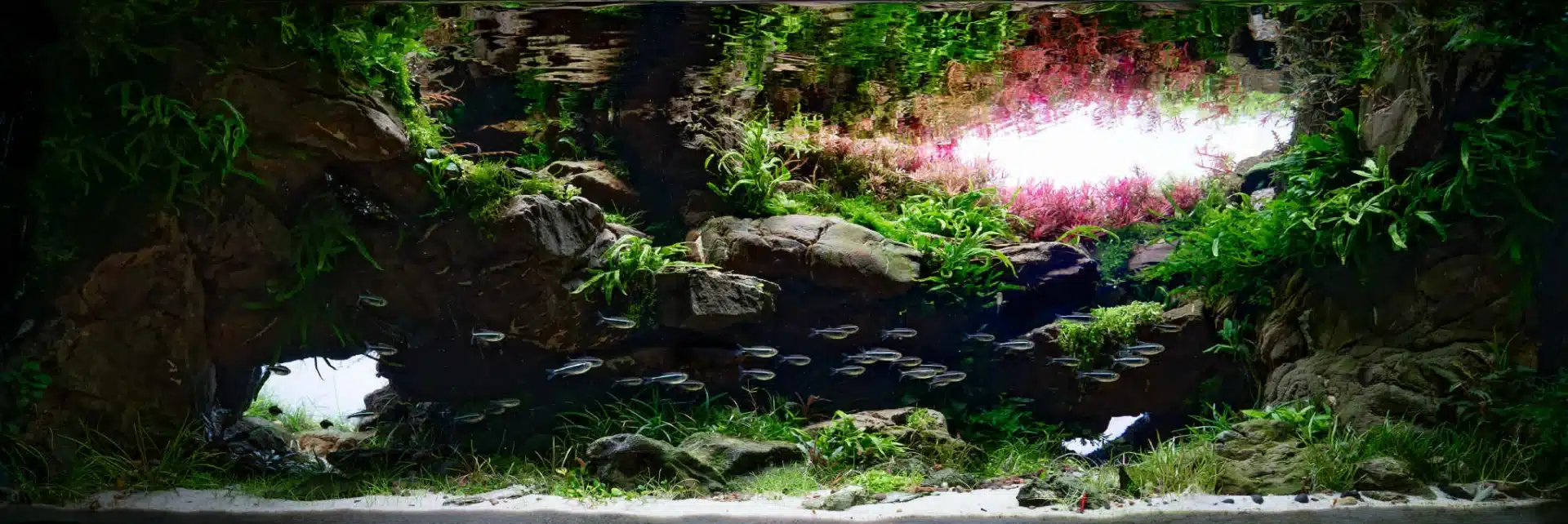

Today we bring you a guest article from Aquascaper Luis Cardoso from Bluviva about what lessons we all can learn from in regards to miniature ecosystems. While not everyone of us can don our gear and jump straight into a beautiful reef every day, maybe some of you will get inspired and give your own miniature ecosystem in a tank at home a go 🙂

Aquascaping Lessons for Divers: What Miniature Ecosystems Teach About the Ocean

If you are both a diver and an aquascaper, you already have knowledge of how both ecosystems can be correlated. A planted tank compresses decades of ecological change into months, and allows you to understand the environment that is not easy to test in real nature. That makes aquascaping a surprisingly powerful training ground, allowing you to understand what is visible on an underwater dive: how life organizes itself around, how invisible microbes keep everything running, and why apparently “stable” reefs or seagrass beds can suddenly crash if there are big changes on their balance.

In this article we will make a parallelism between ocean and aquarium and see what can be learned from it.

1. Hardscape and “foundation species”: from rock piles to reef walls

In aquascaping the main base is hardscape, rock and wood are set to optimize flow, light, shade, hiding spots and grazing surfaces. Marine ecosystems are built the same way, but their “hardscape” is alive and built in a natural way. Ecologists call these structural organisms foundation species, like seagrasses, corals, kelps, that create habitat complexity and support entire communities.

According to Duffy (2006) and supported later by Philipose (2019):

“Ecologists call these structural organisms foundation species, like seagrasses, corals and kelps, which create habitat complexity and support entire communities. Seagrass meadows such as Posidonia oceanica form dense canopies and peat-like sediments that host fishes, invertebrates and epiphytes while stabilising sediments and cycling nutrients (Duffy, 2006). On coral reefs, the calcium-carbonate skeletons of corals literally build the three-dimensional city where reef fish live and feed (Philipose, 2019). These are all natural habitats that are made with time and with no human intervention.”

For divers, your tank offers a scale model of this principle. When you see fish packed around a bommie, a seagrass edge or a wreck, you are watching the same “structure-driven” pattern you create with a dramatic root or rock ridge in an aquascape. Takashi Amano’s Nature Aquarium concept using rock and wood composition to evoke real landscapes can be seen as a parallelism how reef outcrops and seagrass escarpments channel fish movement and behaviour (Amano, 1994).

2. The invisible majority: microbes, holobionts and biofilters

Aquascapers know that without bacteria there is no stability in an aquarium, they are responsible for cycling ammonia, conditioning new setups, stabilising after big maintenance. Marine science is increasingly saying the same about the ocean. In recent studies of marine and aquascaping applications, the authors conclude that “the role of microbial communities emerges as perhaps the most underappreciated factor in both natural ecosystem function and aquascaping success.”

As described in recent scientific literature, several authors have framed marine organisms through the holobiont concept. According to Tarquinio et al. (2019):

“Modern ecology frames marine organisms as holobionts, a combination of hosts plus their microbiome. Tarquinio and colleagues describe the seagrass holobiont, where bacteria on leaves, roots and sediments aid nutrient uptake, produce growth hormones and help defend against disease.”

Grossart et al. further support this idea by showing that:

“Aquatic microbial symbionts drive biogeochemical cycles, from carbon remineralisation to nitrogen transformations, at densities far higher than in surrounding water.”

Apprill (2020) says that: “Symbioses, or associations between different organisms, are plentiful in the ocean and could play a significant role in facilitating organismal adaptations” to changing conditions.

Seen through an aquascaper’s eyes, a coral bed is not a simple rock with polyps, it’s a living filter, a microbial reactor, very much like the biological filter, driftwood and substrate in your tank. Every time you “seed” a new aquarium with mature media, you are supplementing it with lots of bacteria that will provide stability, like the currents and larval dispersal do on the real reefs, moving microbial and invertebrate communities between habitats to stabilize function.

3. Biodiversity across scales: not just “more species = better”

Hobbyists often talk about “stocking lists,” but ecology pushes us to think in terms of functions and levels of diversity. Work on seagrass systems shows that biodiversity stabilises productivity and nutrient cycling, but the type of diversity influences the system (Duffy, 2006; Ren et al., 2022).

There are several relevant scales of diversity to consider like: genetic diversity within foundation species, species diversity within functional groups and habitat heterogeneity at the landscape level. In seagrass beds dominated by one or a few species, different genotypes within the same plant can provide redundancy that buffers against stress. In coral reefs, many species share similar roles (e.g., multiple herbivorous fish) with these options they partially compensate each other. This is where nature balance acts, every host has a role and compensates the other.

If we bring this to aquascaping we can see that: you may only use one stem plant “species,” but mixing cultivars with different growth rates or tolerances mirrors genetic diversity in seagrass; combining several algae-eating species (shrimp, snails, small fish) simulate functional redundancy on reefs and for the last one, creating shaded caves, open sand and dense foliage reproduces habitat heterogeneity that supports more niches and therefore more stable communities.

As a diver, watching which fish live where, or how different herbivores share a reef face, is like observing your clean-up crew behave in the tank, same principle, radically different scale.

4. Tipping points: from cloudy aquarium to collapsed lagoon

Every aquascaper has experienced parameters drift slowly, algae creeps in, everything seems “fine” until one day the water turns pea-soup green and your plants melt. Marine systems experience analogous regime shifts.

The Mar Menor coastal lagoon in Spain is a now-classic example. For decades it absorbed nutrient inputs from agriculture and urban runoff, buffered by extensive seagrass and macroalgal beds. Then, in 2015–2016, a major phytoplankton bloom reduced water transparency so severely that light at the bottom fell below 5% of surface irradiance for at least nine months, triggering the loss of more than 80% of benthic vegetation (Belando-Torrente et al., 2019; Torrente et al., 2019). Like in an aquarium, big changes in the ecosystem can be catastrophic.

On coral reefs, Pendleton et al. (2016) warn that “multiple stressors interact and may affect a multitude of physiological and ecological processes in complex ways.” Ocean warming, acidification, pollution and overfishing do not act independently, they combine to weaken coral–algal symbioses, reduce calcification and shift competitive balances towards algae and bioeroders resulting in big unbalanced conditions.

For divers, this explains why a reef or lagoon can look healthy on one visit and severely degraded a few seasons later. For aquascapers, it is the ecological logic behind regular testing, water changes and avoiding slow, unmonitored nutrient creep that brings balance in a close ecosystem. Tanks and lagoons both teach the same lesson: by the time collapse is obvious, the underlying processes have been off-balance for a long time.

5. What divers can take back into the water

Putting this together, your planted tank becomes more than a decorative hobby; it is a hands-on laboratory that will help you to understand wild nature:

- Look for foundation species. When you drop onto a reef or a seagrass bed, try to understand what is playing the role of “hardscape plus plants” here? Corals, seagrasses, mangrove roots, kelp fronds all are structural engines of biodiversity.

- Remember the microbes. Clear water, lack of odour and steady oxygen in your tank is the result of microbial work. Underwater, sponges filtering, biofilms on seagrass leaves and the skin of fish signal similar invisible communities at work (Tarquinio et al., 2019; Grossart et al., 2013).

- Think in functions, not just species counts. A reef with fewer species but intact herbivores, predators and detritivores may function better than a species-rich but overfished one, every species has its own role in the ecosystem. You can reflect it in a modestly stocked but well-balanced aquascape that can be more stable than an over-crowded “fish soup.”

- Watch for early warning signs. Persistent turbidity, loss of seagrass at depth, frequent bleaching or mass mortalities are the wild-scale equivalent of your tank’s chronic algae film and plant die-back. They indicate problems approaching, not mere cosmetic flaws (Marín-Guirao et al., 2022).

Finally, both aquascaping and diving benefit from the same mindset: curiosity, humility and respect for complexity. Knowledge gaps around complex symbioses and recovery dynamics mean that even carefully designed systems behave unpredictably; experimentation and observation remain essential. That is as true for a 60-litre nature aquarium as it is for a coral atoll.

References (not needed to include it in the article)

Amano, T. (1994). Nature Aquarium World: Book 1. TFH Publications. (openlibrary.org)

Apprill, A. (2020). The role of symbioses in the adaptation and stress responses of marine organisms. Annual Review of Marine Science, 12, 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-010419-010641 (Annual Reviews)

Belando-Torrente, M., et al. (2019). Collapse of macrophytic communities in a eutrophicated coastal lagoon. Frontiers in Marine Science. (Mar Menor case study referenced in Torrente et al., 2019). (ResearchGate)

Duffy, J. E. (2006). Biodiversity and the functioning of seagrass ecosystems. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 311, 233–250. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps311233 (Cambridge University Press & Assessment)

Grossart, H.-P., Riemann, L., & Tang, K. W. (2013). Molecular and functional ecology of aquatic microbial symbionts. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 59. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00059 (PMC)

Marín-Guirao, L., Bernardeau-Esteller, J., Belando, M. D., & Ruiz, J. M. (2022). Photo-acclimatory thresholds anticipate sudden shifts in seagrass ecosystem state under reduced light conditions. Marine Environmental Research, 181, 105732. (ResearchGate)

Pendleton, L. H., Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Langdon, C., & Comte, A. (2016). Multiple stressors and ecological complexity require a new approach to coral reef research. Frontiers in Marine Science, 3, 36. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2016.00036 (Frontiers)

Philipose, K. K. (2019). Artificial reefs. In J. K. Cochran, H. J. Bokuniewicz, & P. L. Yager (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (3rd ed.). Academic Press.

Tarquinio, F., Hyndes, G. A., Laverock, B., Koenders, A., & Säwström, C. (2019). The seagrass holobiont: Understanding seagrass–bacteria interactions and their role in seagrass ecosystem functioning. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 366(6), fnz057. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnz057 (scholar.google.com)

Torrente, M. D. B., Ruiz, J. M., Muñoz, R. G., Segura, A. R., Esteller, J. B., Casero, J. J., et al. (2019). Collapse of macrophytic communities in a eutrophicated coastal lagoon. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, 208. (ResearchGate)